Kim Hart and Dr. Guthkelch -photo by Sue Luttner, Sept. 2015

Dr. A. Norman Guthkelch, the pioneering pediatric neurosurgeon who first proposed in print that shaking an infant could cause bleeding in the lining of the brain, died quietly last week in Toledo, Ohio, a month short of his 101st birthday.

“Until the very end, Norman continued fighting for innocent children and families,” said Kim Hart, his caretaker and colleague and the director of the National Child Abuse Defense and Resource Center (NCADRC), who shared her home with Dr. Guthkelch for the last two years of his life. Last year, just before he turned 100, the two of them helped a local mother regain custody of her twins following a hasty diagnosis of abuse that had ignored the children’s medical histories.

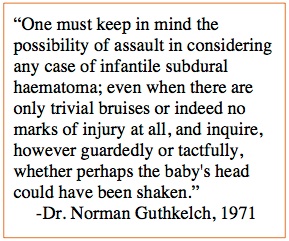

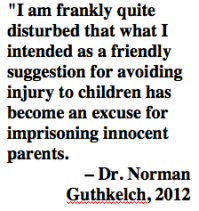

Dr. Guthkelch in 2012

Dr. Guthkelch devoted his final years to working against what he considered a misinterpretation of his work, the model of shaken baby syndrome that has been winning in court for several decades. “I am frankly quite disturbed that what I intended as a friendly suggestion for avoiding injury to children has become an excuse for imprisoning innocent parents,” he told me in an interview in 2012.

Dr. Guthkelch published his groundbreaking paper in the British Medical Journal in 1971, proposing that the shaking of infants, considered at that time a reasonable way to calm or discipline a child in northern England where he was practicing, could be triggering subdural bleeding and endangering brain development. The paper did not propose that subdural bleeding proved abuse, but advised physicians faced with unexplained infant subdurals to “inquire, however guardedly or tactfully, whether the baby’s head could have been shaken.”

When he wrote that paper, Dr. Guthkelch launched an education campaign to stop the practice of infant-shaking in Britain, recruiting the help of case workers who made home visits to new parents. He then pursued other professional interests and didn’t revisit the shaken baby discussion until 2011, when law professor Carrie Sperling with the Arizona Justice Project asked him to review the medical records in the case of Drayton Witt, a father convicted of murder in 2002 for the presumed shaking death of his son.

“I wasn’t too keen on this at first, as I’d retired at least a decade earlier,” Guthkelch sighed in a 2012 conversation, but he examined the records and was “horrified” to discover that 4-month-old Steven Witt had suffered a lifetime of medical problems that could easily explain his death. Dr. Guthkelch’s affidavit helped convince an Arizona state court to vacate the conviction and free Drayton Witt after a decade in prison.

Sperling, now an associate dean at the University of Wisconsin Law School, describes Dr. Guthkelch as “an amazing, gracious man,” who impressed her with “his curiosity, his unassuming nature, and his intellectual integrity.” She characterizes his decision to examine the evidence in the Witt case as “an act of true courage for the man whose work was at the root of the diagnosis.” Ultimately, Sperling says, “What I found most extraordinary about him was his unwavering and unselfish commitment to justice.”

After the Witt case, Dr. Guthkelch made a careful study of the medical records in a series of other shaking convictions in which the defendant still maintained innocence, and in every single case, he told me in a video interview in 2012, he found an obvious, non-abusive medical explanation for the findings. “And I asked myself,” he said, “‘What has happened here?’”

After exploring the medical literature, he concluded that “dogmatic thinking” had set in among child abuse physicians, who had come to believe that a certain constellation of brain findings, including retinal and subdural bleeding, proved abuse. He began articulating his protestations against the common knowledge, in letters to key players and in an essay to accompany an influential 2012 law journal article by a team of attorneys and physicians concerned that shaken baby theory is convicting innocent parents and caretakers.

Dr. Guthkelch advocated abandoning the terms “shaken baby syndrome” and “abusive head trauma,” which incorporate an assumption about mechanism, in favor of the objective term “retino-dural bleeding of infancy.” He tried to encourage communication between the two sides of the debate, he said, “But the arena is much too contentious, and the history too bitter. It’s quite tragic.”

Dr. Guthkelch began his career at a time of tremendous need. During World War II, right after his residency training, he served as an army neurosurgeon—during the Battle of the Bulge, he once told me, he staffed the operating room for 36 hours straight, breaking for food but not for sleep.

After the war, he returned to his studies under pioneering neurosurgeon Sir Geoffrey Jefferson, who had honed his own skills treating head injury during World War I. Away from the battlefield, Guthkelch found himself specializing in the very young. He became Britain’s first physician with the title of pediatric neurosurgeon when he received that appointment at the Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital.

Dr. Guthkelch emigrated to the U.S. in the mid-1970s, working at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh until 1982. He intended to retire at that time, he said, but when he and his wife moved to Tucson, Arizona, the local hospital recruited him for another eight years of practice.

After the death of his wife in 2011 and his experience with the Witt case, Guthkelch focused his energy on the shaken baby debate. “I want to do what I can to straighten this out before I die,” he said in 2012, “even though I don’t suppose I’ll live to see the end of it.”

Moving to Toledo in 2014 gave him the chance to work on the front lines in the fight against the misdiagnosis of abusive head injury. “The 25 months we had with him was an amazing education, an incredible experience, and a true privilege” says NCADRC director Kim Hart. “We are committed to moving forward, championing his desire to correct the misperceptions of his work that have caused so much tragedy for so many innocent families.”

Contributions in memory of Dr. Guthkelch can be made to the National Child Abuse Defense and Resource Center.

For a profile of Dr. Guthkelch from 2012, please see Dr. A. Norman Guthkelch, Still on the Medical Frontier.

For a video interview with Dr. Guthkelch, prepared for a 2013 conference of accused families, please see Conversations With Dr. A. Norman Guthkelch.

For the National Public Radio treatment of his concerns, published in 2011, see Rethinking Shaken Baby Syndrome.

Dr. Guthkelch meets with students from the Medill School of Journalism.

Photo by Alison Flowers, courtesy of the Medill Justice Project

For a review of his concerns regarding shaking theory in the journal Argument & Critique, see Integrity in Science.

For his own informal memoir, also published in Argument & Critique, see Arthur Norman Guthkelch: An Autobiographical Note.

copyright 2016, Sue Luttner

If you are not familiar with the debate surrounding shaken baby syndrome, please see the home page of this site.

He stayed in the field until 1992, as improvements in medical imaging and surgical technique transformed the way doctors diagnose and treat problems of the brain. Neurosurgeons were collaborating with radiologists as they honed their abilities to decipher the lights and shadows of CT scans and MRIs. “I loved every minute of it,” he beams.

He stayed in the field until 1992, as improvements in medical imaging and surgical technique transformed the way doctors diagnose and treat problems of the brain. Neurosurgeons were collaborating with radiologists as they honed their abilities to decipher the lights and shadows of CT scans and MRIs. “I loved every minute of it,” he beams.