Two decisions this fall in Ohio offer hope for the wrongfully accused, while underscoring both the ironies and the complexities of misguided accusations of child physical abuse. One of them even opens the door to possible legal accountability for the casual over-diagnosis of abuse.

First, the Supreme Court of Ohio has reversed the 2016 assault conviction of child care provider Chantal Thoss.

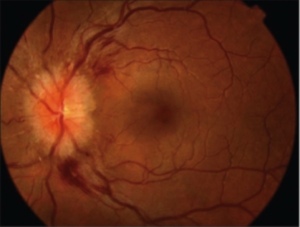

In December of 2014, Ms. Thoss called 911 for help with a baby who she said had fallen from a couch and was “not acting right.” Doctors at the hospital found no bruises, fractures, or other signs of assault, but did find retinal hemorrhages and both new and old bleeding inside the boy’s skull, evidence of both a recent and a preexisting brain injury.

Early in the investigation, Dr. Randall Schlievert at Mercy Health offered his opinion that the baby had been shaken by his last caretaker before the call for help. Detective Brian Weaver never questioned the presumed timing, and the case proceeded against Ms. Thoss.

Early in the investigation, Dr. Randall Schlievert at Mercy Health offered his opinion that the baby had been shaken by his last caretaker before the call for help. Detective Brian Weaver never questioned the presumed timing, and the case proceeded against Ms. Thoss.

According to the court’s summary, Dr. Schlievert explained on the stand “that once the brain is injured, symptoms manifest immediately,” with this concession:

“Schlievert remarked that it is debated in the field whether an older injury can make a child more fragile or more likely to suffer a serious injury from a mild fall later. He noted that many doctors believe that they may have seen such a case, but there is not a single published article that proves that that happens.”

After reading the trial testimony and listening to the 911 call and taped interviews with the babysitter, the three-judge panel declared that a guilty verdict was “against the manifest weight of the evidence.” Noting that they had listened to the same recordings the jury had, the judges offered a different interpretation:

After reading the trial testimony and listening to the 911 call and taped interviews with the babysitter, the three-judge panel declared that a guilty verdict was “against the manifest weight of the evidence.” Noting that they had listened to the same recordings the jury had, the judges offered a different interpretation:

“From those recordings, it is evident to us, acting in this instance as the thirteenth juror, that appellant wholeheartedly believed that she caused injury to E.A. not by shaking him, but by placing him on the couch while retrieving his diaper and by her instinctual response of picking him up off the floor after he had fallen. We could hear the raw emotion in appellant’s voice [emphasis added] as she reported the child’s condition to the 911 operator, the self-condemnation over the decision to briefly leave him unattended on the couch, the genuine surprise upon being informed by Weaver that E.A. had signs of previous injury, and her struggle to understand how this incident produced the injuries suffered by E.A.”

Ms. Thoss has been released from prison. The state has not yet announced whether it will refile charges against her.

A civil case

Meanwhile, Senior District Judge James G. Carr in western Ohio has allowed a civil case against Dr. Schlievert to move forward. Although far from any resolution, the decision is a rare crack in what is usually a solid wall of immunity for physicians who diagnose child abuse.

In September of 2014, day care worker Beth Gokor called her supervisor to report that a 3-year-old boy she was watching couldn’t walk or stand on his own after slipping and falling on a wet linoleum floor.

In September of 2014, day care worker Beth Gokor called her supervisor to report that a 3-year-old boy she was watching couldn’t walk or stand on his own after slipping and falling on a wet linoleum floor.

At the hospital, the boy told a physician’s assistant that he “slipped and fell,” and a co-worker later confirmed Gokor’s report that the floor was wet from a recent mopping. According to police notes, the child’s mother said he had told her he slipped while running.

When Dr. Randall Schlievert reviewed the records, however, he concluded that the spiral fracture to the boy’s leg must have been an inflicted injury, not an accident—and he recommended challenging the day care’s license because “[c]hildren do not appear to be currently safe there.” Schlievert offered his opinion that the day care was making “improbable statements” and asserted, as if refuting the caretaker’s report, “[JJ] would not have been able to stand.”

When Dr. Randall Schlievert reviewed the records, however, he concluded that the spiral fracture to the boy’s leg must have been an inflicted injury, not an accident—and he recommended challenging the day care’s license because “[c]hildren do not appear to be currently safe there.” Schlievert offered his opinion that the day care was making “improbable statements” and asserted, as if refuting the caretaker’s report, “[JJ] would not have been able to stand.”

Ms. Gokor was fired immediately, and she was later charged with endangering children.

Her defense team hired pediatric radiologist Gregory Shoukimas, who, according to the court summary, not only concluded that the injury was accidental but also noted that Dr. Schlievert’s report was “riddled with errors.”

When prosecutors received the alternative medical report, the state dropped charges against Ms. Gokor, who then filed a civil suit against Dr. Schlievert. The decision this fall rejected a motion by Dr. Schlievert to block that suit, which will presumably now move forward.

A similar suit

Intriguingly, the same judge who gave the green light to the Gokor suit this year blocked a similar suit in 2017, also against Dr. Schlievert and also pressed by criminal defense attorney Lorin Zaner, a veteran of wrongful abuse cases.

The plaintiff in the earlier decision was Molly Blythe, the mother of twin daughters born prematurely, as many twins are. The second-born twin, referenced as “KB,” endured first manual repositioning and ultimately vacuum extraction, emerging with “significant bruising” on her scalp. At early visits with the pediatrician, the mother expressed ongoing concerns over KB’s frequent vomiting and difficult sleep patterns.

At the age of two months, with her head growing unusually fast, KB was found to have bilateral subdural hematomas and large extra-axial fluid collections. Doctors performed surgery to relieve the brain pressure. The first eye examination, conducted after the surgery, revealed retinal hemorrhages,.

“In the absence of any other explanation, the doctors diagnosed KB with Shaken Baby Syndrome,” the judge’s opinion recounts, and the county hired Dr. Schlievert to perform a formal child abuse assessment. “After reviewing KB’s medical file,” the judge wrote, “Dr. Schlievert concurred in the initial child abuse diagnosis.”

Mr. Zaner hired a full complement of experts—a neuroradiologist, a diagnostic radiologist, a pediatric opthalmologist with a specialty in retinas, a pediatrician with extensive child abuse experience, and a biomechanics professor. After receiving their reports, which enumerated other possible causes for the findings, the state dropped criminal charges. Rather than engage in further court proceedings, the mother consented to a family court order giving custody of the girls to their maternal grandmother. Then she filed suit against Dr. Schlievert and the county.

In his opinion blocking that suit, Judge Carr emphasized that Dr. Schlievert’s conclusions matched those of the treating physicians:

“The fact that Dr. Schlievert reached nearly identical conclusions supports a determination that his conduct did not ‘shock the conscience’ but rather was a sound medical conclusion based on his review of KB’s medical file.”

In its insistence that Dr. Schlievert was innocent of intentional misdirection, the opinion seems to sanction his apparent decision to finalize his abuse assessment in the case of a 2-month-old preemie without examining the birth records or establishing a clear timeline for the reported findings:

“The complaint does not allege that at the time he provided his February consultative report to CSB [Children’s Services Board], Dr. Schlievert knew about the traumatic birth or that the surgeries had preceded the first, and thus baseline, retinal examination.”

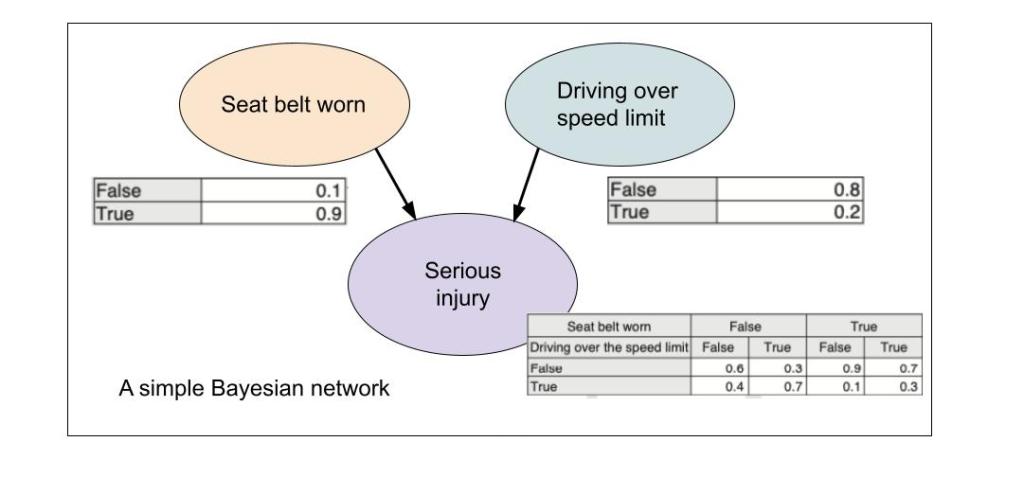

I can understand why the unanimity of opinion among child abuse experts gives the impression that shaking theory is well established—that conclusion, alas, is one of the reasons this fight is so difficult. The problem is that shaking theory was adopted before it was proven scientifically, and the research since that point has been premised on the assumption that convictions and plea bargains prove abuse.

My best hope is that Judge Carr might notice a pattern in the child abuse suits that come through his court. A few popular but unproven tenets of child abuse medicine—that the triad proves shaking, for example, and the symptoms are always immediate, or that spiral fractures mean abuse—continue to derail accurate diagnosis and mar the good work that child abuse physicians otherwise do.

copyright 2018, Sue Luttner

If you are not familiar with the debate surrounding shaken baby syndrome, please see the home page of this blog site.

Early in the investigation, Dr. Randall Schlievert at Mercy Health offered his opinion that the baby had been shaken by his last caretaker before the call for help. Detective Brian Weaver never questioned the presumed timing, and the case proceeded against Ms. Thoss.

Early in the investigation, Dr. Randall Schlievert at Mercy Health offered his opinion that the baby had been shaken by his last caretaker before the call for help. Detective Brian Weaver never questioned the presumed timing, and the case proceeded against Ms. Thoss. After reading the trial testimony and listening to the 911 call and taped interviews with the babysitter, the three-judge panel

After reading the trial testimony and listening to the 911 call and taped interviews with the babysitter, the three-judge panel  In September of 2014, day care worker Beth Gokor called her supervisor to report that a 3-year-old boy she was watching couldn’t walk or stand on his own after slipping and falling on a wet linoleum floor.

In September of 2014, day care worker Beth Gokor called her supervisor to report that a 3-year-old boy she was watching couldn’t walk or stand on his own after slipping and falling on a wet linoleum floor. When Dr. Randall Schlievert reviewed the records, however, he concluded that the spiral fracture to the boy’s leg must have been an inflicted injury, not an accident—and he recommended challenging the day care’s license because “[c]hildren do not appear to be currently safe there.” Schlievert offered his opinion that the day care was making “improbable statements” and asserted, as if refuting the caretaker’s report, “[JJ] would not have been able to stand.”

When Dr. Randall Schlievert reviewed the records, however, he concluded that the spiral fracture to the boy’s leg must have been an inflicted injury, not an accident—and he recommended challenging the day care’s license because “[c]hildren do not appear to be currently safe there.” Schlievert offered his opinion that the day care was making “improbable statements” and asserted, as if refuting the caretaker’s report, “[JJ] would not have been able to stand.”

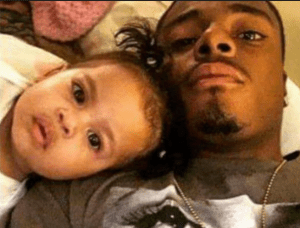

The jurors who found Flores innocent heard about Mason’s complex medical history, and the new brain bleeds that appeared while the boy was in the hospital and then again in foster care. On the interrogation tape, however, long before anyone had looked at past medical records, the detectives never waver from confidence in the father’s guilt. Ignoring Flores’s obvious pain and confusion, they reject his story again and again, prodding him to quit lying and “accept responsibility.” Even when he breaks down and accepts their accusations, Flores says only that he “might have” rocked the boy harder than he realized, he doesn’t remember.

The jurors who found Flores innocent heard about Mason’s complex medical history, and the new brain bleeds that appeared while the boy was in the hospital and then again in foster care. On the interrogation tape, however, long before anyone had looked at past medical records, the detectives never waver from confidence in the father’s guilt. Ignoring Flores’s obvious pain and confusion, they reject his story again and again, prodding him to quit lying and “accept responsibility.” Even when he breaks down and accepts their accusations, Flores says only that he “might have” rocked the boy harder than he realized, he doesn’t remember.

In South Carolina, meanwhile, Wayne County dropped charges against an accused father who’d been in jail for two years—and indicted the babysitter instead. As summarized by reporter Angie Jackson in

In South Carolina, meanwhile, Wayne County dropped charges against an accused father who’d been in jail for two years—and indicted the babysitter instead. As summarized by reporter Angie Jackson in  The indictment of the babysitter, Jackson wrote, “does not detail the evidence against her.” I speculate that the key point is whether the effects of a serious pediatric head injury are or are not immediately obvious, a question still under debate in the

The indictment of the babysitter, Jackson wrote, “does not detail the evidence against her.” I speculate that the key point is whether the effects of a serious pediatric head injury are or are not immediately obvious, a question still under debate in the